It’s time to rethink Midland’s overuse of PD zoning

When you buy a house or open a business, zoning determines not just what you can do with your property but also what can be built next door. It shapes how neighborhoods grow, how traffic flows, and what kinds of development go where. That makes Midland’s zoning decisions relevant to every resident.

Most of the city falls under standard zoning, meaning properties are categorized as residential, office, retail, or industrial. These categories come with clear, pre-set rules. Property owners know what’s allowed, and neighbors know what to expect. But zoning doesn’t just impact existing buildings. It also affects whether land gets developed. If the zoning is too restrictive or out of sync with market demand, lots can sit vacant.

In April, council reviewed a request to rezone a vacant property on Big Spring Street from office use to regional retail. Office zoning is for low-traffic uses like law or medical offices. City staff noted that Midland has a surplus of empty office space, which likely discouraged development. Council approved the change to regional retail, which allows for restaurants, convenience stores, and service shops.

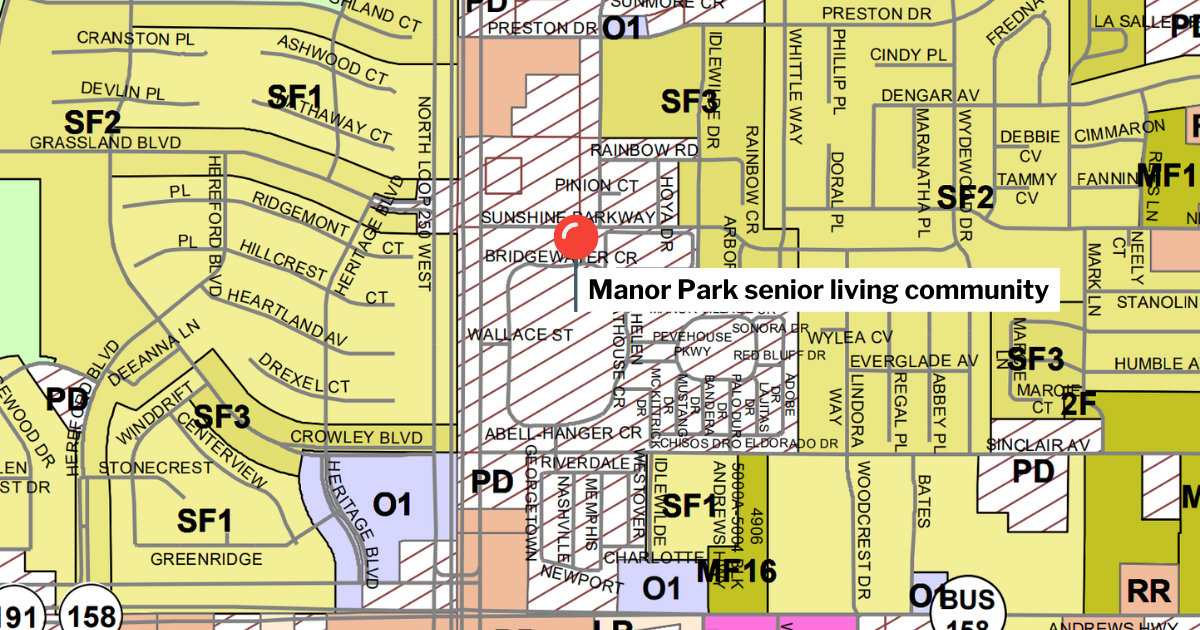

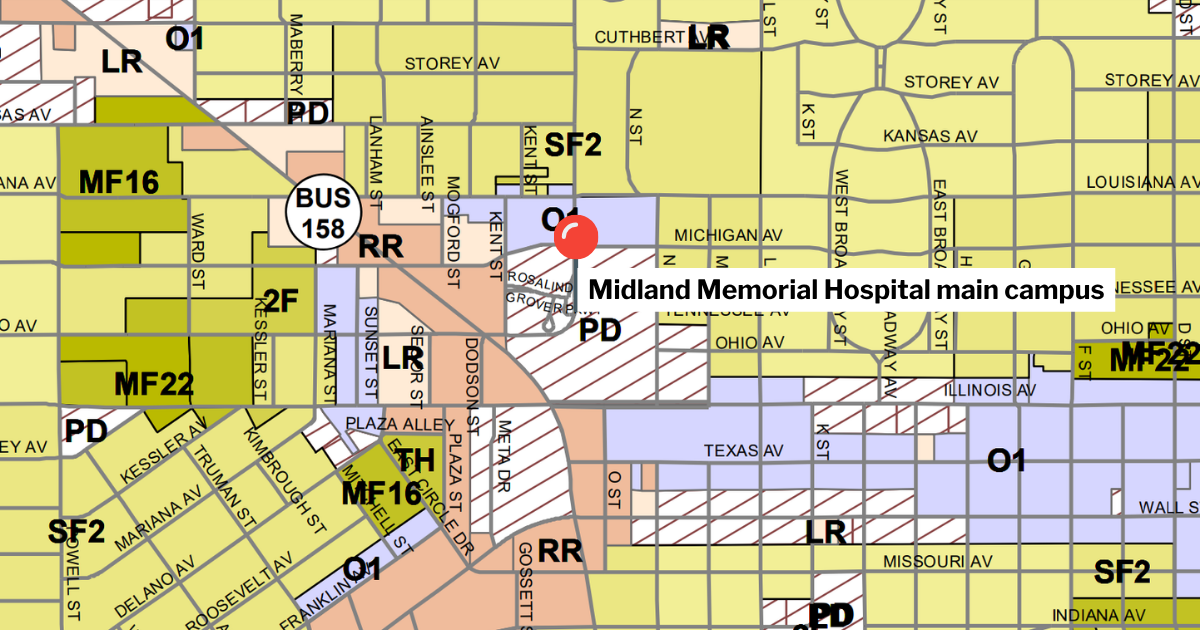

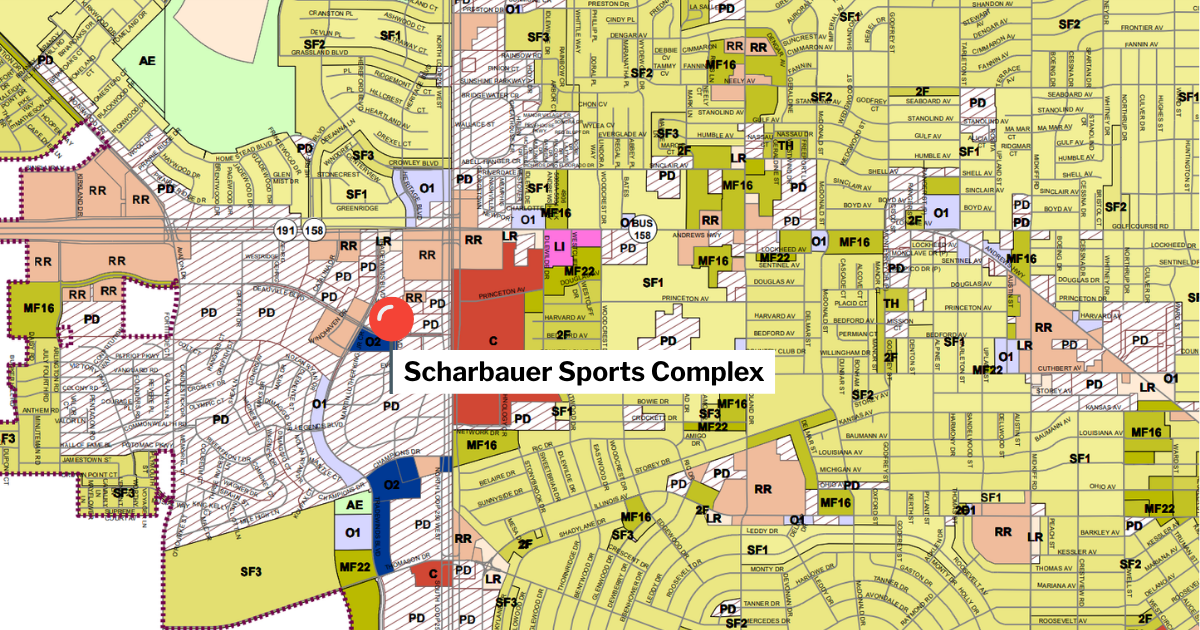

Planned Developments (PDs) work differently. PDs are intended for unique projects that don’t fit standard zoning. Instead of applying standard rules, the city and developer negotiate a custom set of conditions, like building placement, parking lot size, and even permitted land uses. Midland examples include the Scharbauer Sport Complex, Manor Park, and Midland Memorial Hospital. These specialized sites benefit from tailored rules.

PD zoning would also make sense for the future Omni hotel, a $170 million public-private investment. Under its current central business zoning, the area surrounding the hotel could make way for a car wash or a funeral home, hardly appropriate neighbors for a flagship hotel.

While PDs can serve a purpose, they aren’t always necessary. Some of Midland’s newest specialty projects aren’t zoned PD. Zoo Midland sits on agricultural-use land, which already allows zoo use. The Preserve is zoned local retail, allowing for a mix of office, dining, and shopping.

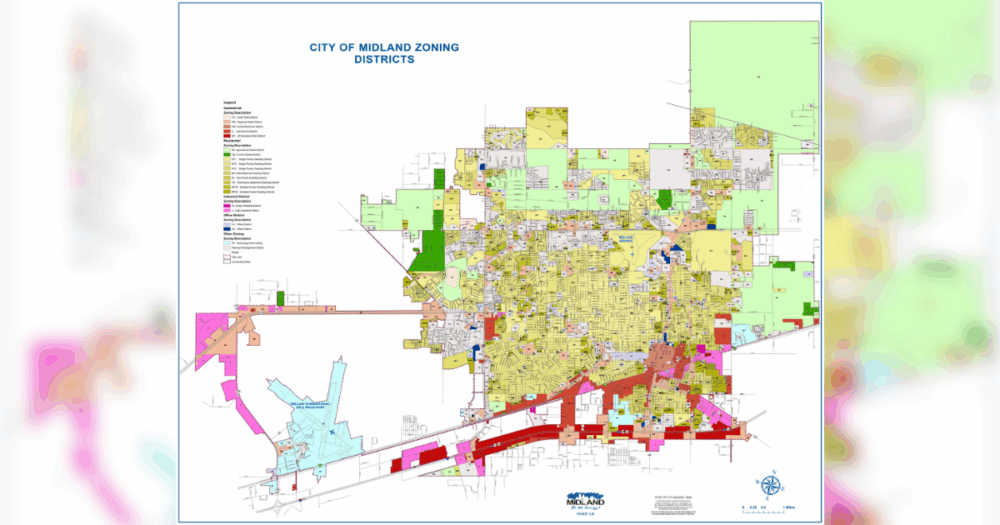

In fact, Midland has gone far beyond the special-use intent of PDs. PDs now cover broad areas where standard zoning would suffice. The city’s zoning map shows a patchwork of PDs, many overlapping typical commercial or residential zones.

This isn’t just messy, it’s confusing. The city’s Tall City Tomorrow comprehensive plan warns that the “abundant use of PDs has created inconsistent design patterns and left many developers unsure of the city’s expectations.”

PD zoning resurfaced at the Sept. 23 council meeting. A developer asked to rezone a vacant two-acre lot along Loop 250. The property was zoned PD for housing. City staff recommended local retail to buffer the nearby neighborhood. The developer requested regional retail, a broader, more flexible designation, which council approved.

Former Planning and Zoning Chairman Bo Zertuche explained how PDs became overused. “We were trying to make things happen,” he said. “The vehicle that we found to help us with that was with PD.” But he emphasized PDs were never meant to give the city broad control over private development.

Engineer John Newton agreed. He told council that standard zoning is now the “preferred and more streamlined approach.” Mayor Lori Blong also noted that excessive restrictions can hurt development. “This higher level of regional retail gives [the developer] the greatest opportunity for marketing,” she said.

Midland has already approved funding to update the Tall City Tomorrow plan. That’s the right time to revisit how PDs are used. They should be reserved for truly unique projects and not used to micromanage development. For everything else, standard zoning provides clarity, consistency, and flexibility for landowners and developers.

Midland can’t afford to repeat outdated zoning practices. Council should reduce its reliance on PDs and adopt a simpler, more predictable approach to growth.