A small fee, a big reaction: inside Midland’s drainage vote

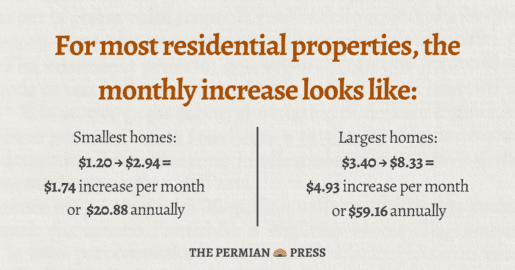

What happened: The Midland City Council approved a drainage utility fee increase on second and final reading Tuesday, Jan. 27. The changes raise most residential bills by about $2 to $5 per month and took effect on Monday, Feb. 1. The measure passed 6–1, with Councilwoman Robin Poole voting against it. The first reading passed 6–0, with Poole absent.

Why it matters: Some have questioned the $2–$5 monthly increase to an existing infrastructure fee, citing affordability and legality concerns, making it important to clearly understand what the fee funds and how Midland’s drainage system works.

Reality check: Several claims made about the fee during public comment deserve clarification:

-

Claim: tax businesses instead – One speaker opposed the $2–$5 monthly increase for residents and urged higher taxes on businesses. The speaker later acknowledged the economic reality that higher business taxes would pass on to consumers.

- Claim: a fee must be voluntary – Texas municipal drainage utilities are mandatory by design and are assessed based on impervious cover and drainage impact. Whether a charge is voluntary is not how Texas law distinguishes a fee from a tax.

-

Claim: this is a 145% increase – Percentage increases can sound dramatic, but they obscure scale. For most households, the increase amounts to $2-$5 per month.

-

Claim: the fee is illegal – One speaker cited Texas Local Government Code Chapter 552 and argued that the fee cannot “[subsidize] school projects or city contracts that weren’t put to a vote.” The state does not prohibit funding drainage infrastructure integrated with roadways, particularly school roadways, in this case. Whether a fee constitutes an unlawful tax depends on how the city uses the funds and on whether the funds remain connected to drainage services.

-

Claim: put it to the voters – Midland residents elect council members to make decisions on their behalf. Requiring a public vote for every adjustment would undermine representative government.

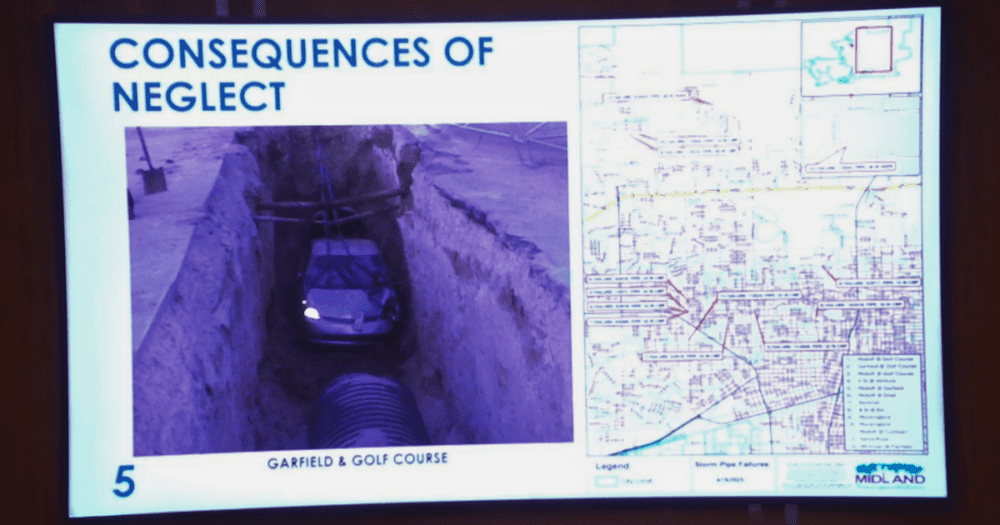

The big picture: City staff said Midland has documented drainage and street infrastructure problems for decades, with tens of millions of dollars in unmet needs. Much of the issue stems from aging corrugated metal pipe installed in the 1970s. Over roughly 15 years, the city has documented 13 sinkholes caused by failing pipe. The city estimates that replacing those sections alone will cost $18 million.

Staff also explained why they tie drainage to streets in Midland. The city has about 670 miles of roadway, but only 70 miles of storm drain pipe. Because Midland is mainly flat, roadways themselves act as part of the drainage system, carrying stormwater along curbs and gutters to collection points.

Go deeper: Councilman John Burkholder asked how the city ensures it uses drainage fees appropriately. Staff said they hold the fees in a separate fund and review each project to determine what portion qualifies as drainage-related. Councilman Brian Stubbs noted that an auditor publicly reviews fund activity each year.

Since the city implemented the drainage fee in 2018, it has collected about $17.3 million in total, or roughly $2 million per year. According to staff, the fund balance typically sits at around $1 million because they spend the revenue each year on projects, which they said is not enough to keep up with growth and backlog needs.

Looking ahead, the city identified about $135 million in drainage and street needs over the next 10 years and nearly $200 million over 20 years. Even with the rate increase, the city expects drainage fees to generate about $7.3 million annually, which will require additional funding sources.

The other side: Much of the controversy centers on infrastructure tied to two new Midland ISD high schools, which accelerated projects already in the city’s long-range plans. City staff said total infrastructure costs tied to the campuses total $28.5 million. MISD’s contribution increased from about $4 million to roughly $9.4 million through negotiations. Additional offsets included water fund contributions and permit fees, leaving the city responsible for about $13.5 million.

What’s next: Council directed staff to return in 12 to 18 months with an audit of drainage utility revenue and spending, a review of how the city used funds, and potential adjustments, if warranted.