Residents sue YMCA, Bynum, City of Midland over road access

Editor’s note: The photo above shows a “Private Road” sign that Llano Estacado residents placed on a City of Midland speed-limit sign amid an ongoing road-access lawsuit.

What happened: Sixteen of about 45 Llano Estacado households have sued the City of Midland, the YMCA of Midland, and Bynum School. The petition, filed Aug. 28 in the 441st District Court, seeks to stop the defendants and the public at large from using Golden Gate Road and Avalon Road.

The plaintiffs argue that the city and the public have used the subdivision’s roads without authorization and that no formal dedication of the streets to public use ever occurred. The lawsuit also requests at least $250,000 in monetary relief, along with attorney fees and court costs.

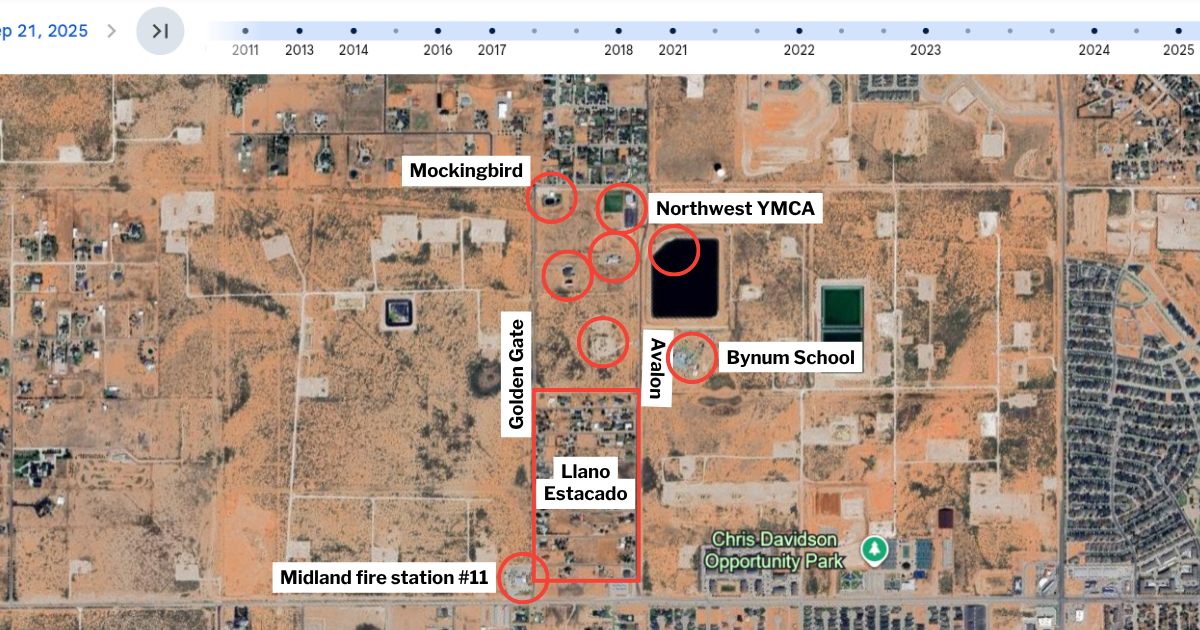

Why it matters: Golden Gate and Avalon are the most direct routes to Bynum School, which opened in 2018 and serves about 120 children and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and to the Northwest YMCA, which opened in 2025. The city’s Fire Station No. 11, completed in 2023, also has two entrances on Golden Gate.

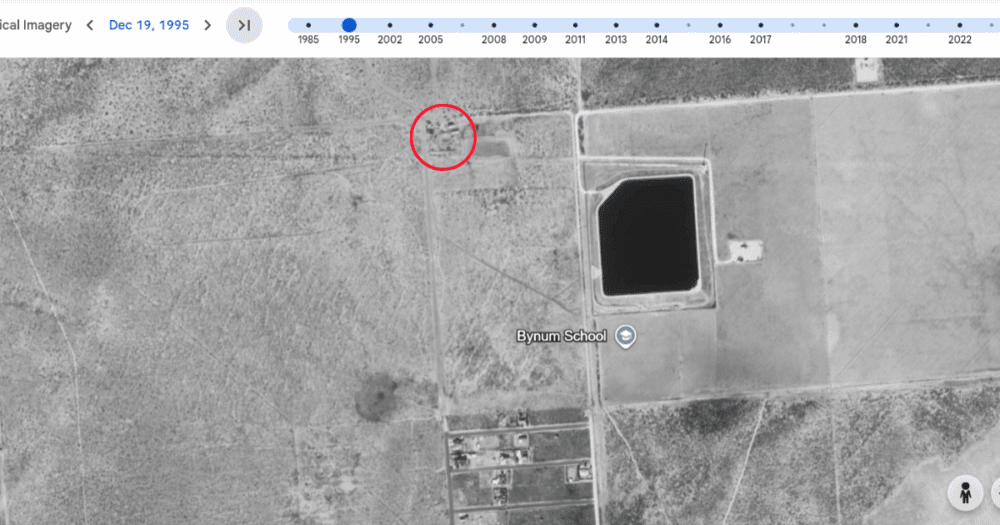

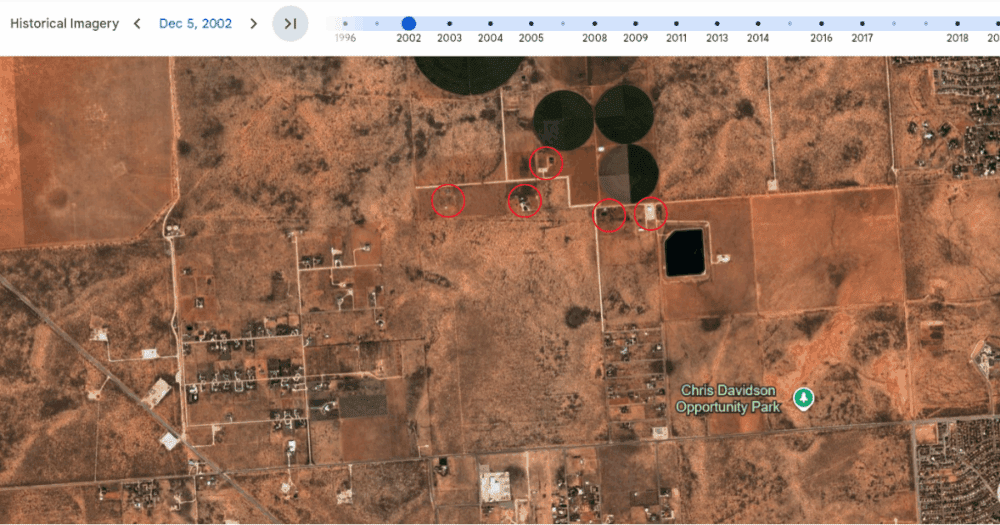

At least eight properties outside of the subdivision (each circled in the image below) that use Golden Gate or Avalon for access, as well as multiple other residents north of Mockingbird Lane who may use Golden Gate or Avalon to access their homes. The historic satellite imagery below shows how the area developed. In 1995, one property north of the subdivision appeared to rely on Golden Gate for access. By 2002, at least five properties did.

- 1995 Google Earth satellite imagery

- 2002 Google Earth satellite imagery

Go deeper: Llano Estacado’s 1965 restrictive covenants, recorded in 1981, describe the streets as easements for owners and guests but explicitly allow public dedication of the streets. The document does not state that the streets must remain private in perpetuity.

“Nothing herein shall prevent the owners of said tracts from dedicating any such street or alley easement to the public as a street or alley,” the covenants state.

In Texas, streets can become public not only through formal dedication but also through what courts call implied dedication. That can occur when owners allow long-term public use and the city provides services such as maintenance, signage, or utilities.

Texas courts have recognized implied dedication in multiple cases, including O’Connor v. Gragg (1960), Las Vegas Pecan & Cattle Co. v. Zavala County (1984), and Lindner v. Hill (1985), which held that long-standing public use and governmental service can establish public status even without a recorded dedication document.

The big picture: At the time of publication, the court has not scheduled a hearing, and the City of Midland, YMCA, and Bynum School have not yet filed formal responses. The information above reflects what is currently available through public court filings, deed records, and satellite imagery.

The petition does not specify how restricting access would work in practice. It does not indicate whether residents would gate or otherwise physically close the streets, who would pay for or enforce any access controls, or how services such as mail delivery, trash collection, and utility work would continue for the subdivision and the properties north of it that rely on Golden Gate and Avalon.

The filing states that increased public traffic has interfered with residents’ “peace and use and enjoyment” of the roads and that residents maintain the streets “at their own expense.” The publicly available court filing does not include documentation of traffic impacts or maintenance activities. The petition also asks the court to “maintain the status quo,” but does not define what the plaintiffs mean by that term.

The bottom line: The lawsuit asks the court to determine whether Golden Gate and Avalon should continue to function as public access routes, or whether a portion of subdivision residents may limit use of the roads.